Light is the foundation of every good image. Painters knew that long before film existed. They studied how light wraps around form, how it affects mood, and how it can make something ordinary feel alive. Before cinematographers had cameras or color grading, painters were already experimenting with value, tone, and atmosphere.

When I study painters who mastered light, I always come back to the same names: John Singer Sargent, Joaquín Sorolla, Claude Monet, and Alfred Munnings. They each had their own approach, but what connected them was their ability to translate light into emotion. They didn’t just record what they saw; they designed it. That is what makes their work feel timeless.

John Singer Sargent

Sargent painted as if light was a sculptural tool. You can see it in the way he built a portrait, blocking in the biggest shapes first and then carving form through subtle value changes. He had an incredible sense of restraint. Nothing was overworked. The softness of an edge or a single flick of highlight across a cheekbone could describe an entire structure. Standing in front of one of his paintings at the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, it is easy to forget that you are looking at paint. He created a sense of immediacy that feels alive, almost cinematic.

Joaquín Sorolla

Sorolla worked differently but with the same goal: to capture the experience of light. His paintings of figures on the beach in Valencia are flooded with sunlight. The whites are rarely pure white. They vibrate with warm yellows and cool blues. Shadows are not dead zones; they are filled with reflected color. You can feel the weight of the air and the shimmer of water. That sensitivity to atmosphere is what makes his work so powerful. He was painting not just what light looked like but what it felt like to stand in it.

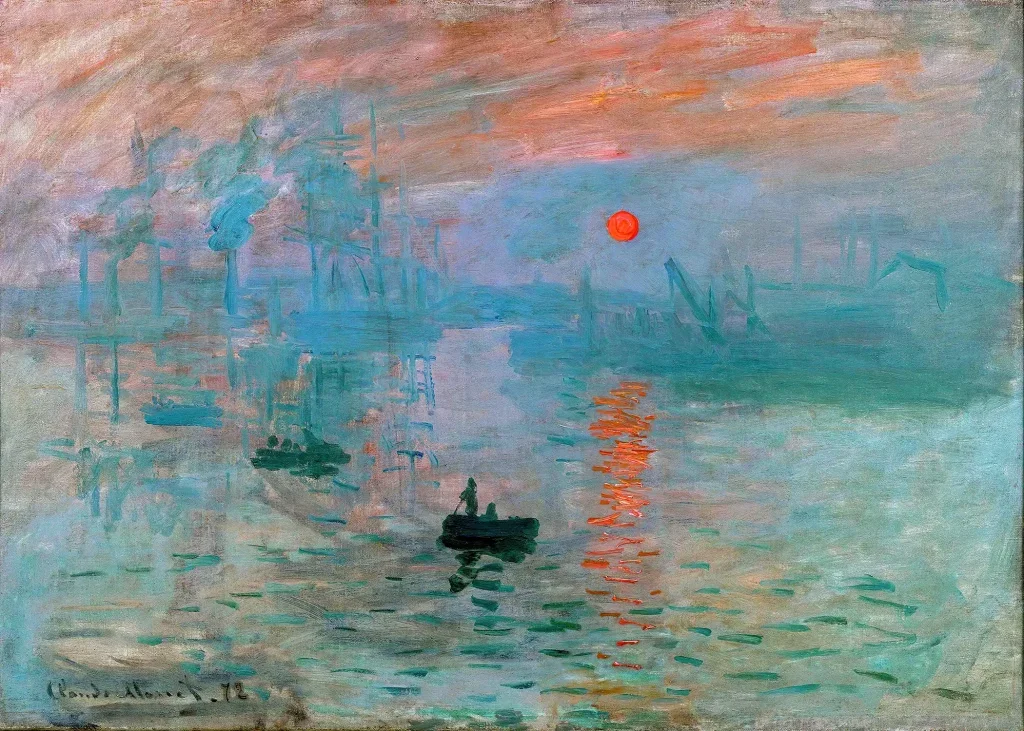

Claude Monet

Monet took that idea further by studying how light changes over time. He would paint the same cathedral or haystack at sunrise, noon, and dusk, each time chasing a different version of truth. He wasn’t interested in precision but in perception. He painted color relationships, the way a warm sky influences the ground or how mist softens form. That understanding of relative color and temperature has shaped everything from impressionism to modern cinematography.

Alfred Munnings

Munnings, often remembered for his equestrian scenes, brought the same respect for light to movement. His outdoor paintings capture fleeting gestures and moments, yet they always feel structurally sound. Horses gleam with the bounce of sunlight, trees filter light across figures, and the color of dust hangs in the air. Munnings had a deep understanding of form and anatomy, but it was his handling of light that gave his subjects energy and truth.

I have spent years studying these painters, not to imitate them but to understand their thinking. Each one treated light as architecture. It defined everything else. When you paint, you learn that form is only visible because of light. The structure of a face, the curve of an arm, or the mass of a building all depend on how light falls across them. You start to think in values instead of outlines. That mindset transfers directly to film.

In visual storytelling, light still serves the same purpose. It directs the eye, sets the tone, and defines space. A filmmaker uses light the same way a painter does: to build emotion and guide attention. When you look at great cinematographers, you can trace their approach back to painters. Think of Roger Deakins and the way he composes with soft contrast, or Emmanuel Lubezki’s use of natural light in long takes. Both rely on value control, edge variation, and composition that comes straight out of the painter’s toolkit.

Painting trains the eye to simplify. You learn to reduce complex scenes into patterns of light and shadow, to find what really matters. That kind of clarity is essential when designing a sequence for film. Shooting boards, for example, rely on that discipline. A good board artist doesn’t draw everything. They draw only what the audience needs to see. The shapes of light and dark are what make the shot readable, especially in fast-moving action.

When I work on a shooting board, the same lessons apply. Each frame must communicate instantly. It has to make sense to the director, the cinematographer, and the crew, all while serving the story. I often think about how Sargent simplified complexity through light, or how Sorolla used edges to keep energy in a scene. Those ideas carry over directly. The same visual logic that makes a painting feel believable makes a film sequence feel coherent.

Light is also a storytelling device. It defines emotion and rhythm. Painters have always known that. The way light touches a subject changes the entire tone. A face half in shadow suggests mystery. A scene filled with low, warm light feels nostalgic or safe. Harsh overhead light creates tension. These are not just aesthetic choices. They are narrative tools. Painters mastered them first, and filmmakers continue to build on those foundations.

At the Nelson-Atkins Museum, I like to get right up close to a painting and study the brushwork. Up close, it’s often shockingly simple… just one confident swipe of paint for a nose. Then you step back, and suddenly it all makes sense. That mix of looseness and control is exactly what I aim for in visual development.

Painters like Sargent and Monet were essentially doing what filmmakers do now. They observed life, analyzed how light behaved, and then used that knowledge to tell a story through visual choices. They were designers of reality, shaping it to make it feel more true. The better you understand their methods, the better you can control mood and meaning in film.

In both painting and film, the real craft lies in subtlety. Most people watching a movie won’t consciously think about the light, but they will feel it. Just as someone standing in front of a Sargent portrait feels the presence of the sitter without knowing why, a movie audience senses tension, warmth, or isolation through lighting choices that were carefully planned.

Years of traditional study taught me that good lighting is about restraint. You do not need to show everything. You need to reveal just enough. Painters knew this instinctively. They let the viewer’s eye do some of the work. The same is true in film. A frame that shows too much loses focus. A frame that controls value relationships pulls the viewer exactly where you want them to look.

That control of attention is what makes a sequence readable and emotionally strong. Whether it is a single painted portrait or a fast-cut action scene, the principle is the same: light shapes meaning.

I often encourage younger entertainment artists to study classical painting, not just film frames. The old masters figured out every visual problem we still face today. How to show form. How to use color temperature to create depth. How to balance composition so the eye flows naturally through the scene. Once you learn those lessons from paint, you start to see them everywhere… in photography, in animation, in cinema.

The longer I work in this field, the more I realize that painting is the purest form of visual problem-solving. It strips away dialogue, editing, and movement and leaves you with only value, color, and shape. If you can tell a story with those, you can tell it anywhere.

Studying painters like Sargent, Sorolla, Monet, and Munnings isn’t about nostalgia. It is about keeping craftsmanship alive. They built the foundation that all visual storytellers still rely on. Every time I paint or draw a sequence, I am applying what they discovered centuries ago… how light reveals truth, form, and emotion.

Light is both science and poetry. It obeys physics but expresses feeling. The more you study it, the more you realize how much it controls everything we see and feel in an image. That is what connects fine art and film at the deepest level. They both depend on the same language of light.

📩 Reach out: paul@paultemplestudios.com

🎨 Explore more: www.paultemplestudios.com

Want more blog posts on this topic?

1. From Traditional Painting to Preproduction: How Fine Art Roots Shape Visual Storytelling

2. How Classical Painting Shaped Modern Filmmaking

3. Carrying the Legacy of Film Illustrators Forward